5 minute read

The Department of Health and Human Services recently released their new health workforce strategic plan. There is a lot of good information here. I’ll share a few thoughts below. The plan is worth looking over and will undoubtedly inform future federal spending in workforce development.

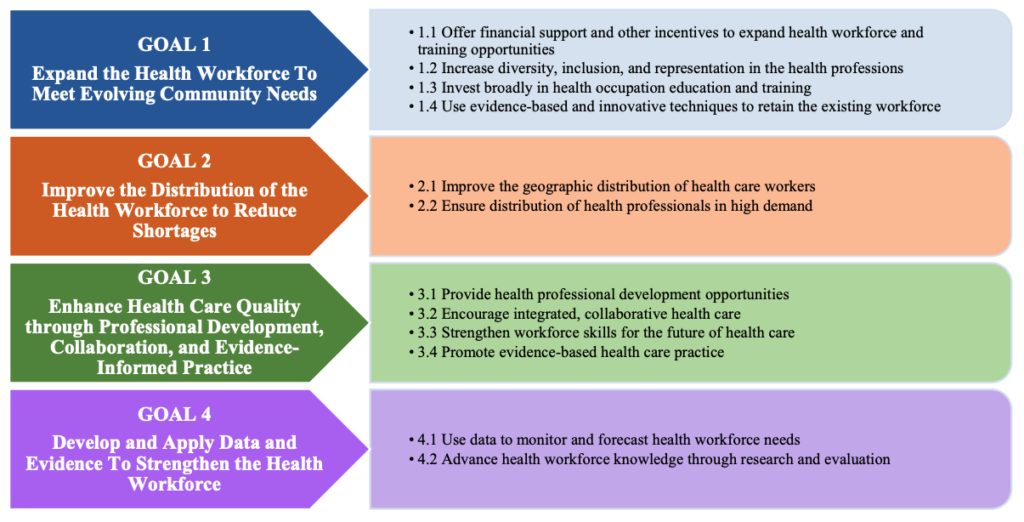

The new plan has four goals: expand supply; ensure equitable distribution; improve quality; and improve outcomes using data-informed and evidence-based strategies. See the graphic below from the plan.

First, expanding supply. My own guild has worked for years to become recognized by Medicare. Expanding the Medicare behavioral health workforce to include marriage and family therapists, mental health counselors and peer support specialists will dramatically expand access to lifesaving care for Medicare beneficiaries. Urge your legislators to cosponsor and support the passage of the Mental Health Access Improvement Act (S. 828/H.R. 432) and the Promoting Effective and Empowering Recovery Services (PEERS) in Medicare Act (S. 2144/H.R. 2767).

Communities need healthcare professionals who use a biopsychosocial lens in treatment and who can easily integrate with interdisciplinary care teams. Expanding supply should also include an increase in spending for integrated care education and training.

Second, matching demand with supply. Telehealth exploded during the pandemic and increased access for patients in underserved areas. Yet, there are still major shortages. Many patients are waiting months for mental health services. Integrating medical and behavioral health providers can help. Increasing funds for scholarship and loan repayment programs can encourage more graduates to live and work in underserved areas.

Current workforce prediction approaches are outdated, making it difficult to match demand with supply. Healthcare systems typically use only internal productivity data to determine where new behavioral health services may be needed. This approach is limited because it excludes social determinants of health and state-wide data and fails to use predictive mathematical models. Government agencies and staffing organizations rely on the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) health professional shortage area (HPSA) data platform to determine workforce shortages. The HRSA HPSA platform relies on facility self-enrollment, does not include key health disparity datasets, does not report medical specialties beyond primary, dental, and mental health, and does not indicate where medical and behavioral services are integrated. Employers need a more sophisticated and precise workforce mapping system to predict and match the rising behavioral health needs in Arizona.

Third, improve quality. This is where CFHA and other integration-focused organizations can focus efforts. We can share our expertise in building or transforming practice to become more integrated. We can also push for more empirical evidence demonstrating the effectiveness and implementation science of integrated care. Currently, the evidence base is still relatively small.

Fourth, use data-informed and evidence-based strategies to accelerate workforce development. See the paragraph above on more sophisticated workforce mapping systems. Staffing is an expensive and time-consuming process. We need more information on how long it takes to recruit, hire, and onboard new integrated care workers. Delays in staffing contribute to delays in patient care and reimbursement. There is strong research potential in better understanding how to accelerate the onboarding process in our field.

It is encouraging to see a detailed workforce plan like this one from HHS, especially one with clear calls for more integration and collaboration. Hopefully new funds support the realization of these ideas.

Leave a Reply