3 minute read

Last week, the number of infections reported to the World Health Organization dropped for the third week in a row. Here in the US, recent reports suggest that numbers are dropping as well. The number of new daily coronavirus cases has dropped below 100,000 for the first time this year, according to data from Johns Hopkins University. As vaccines continue to rollout, hopefully this trend will continue.

This news should be celebrated, especially after a long year of political turmoil and economic devastation. The coronavirus pandemic has been a public health emergency with tremendous social and economic disruptions. Recommended preventive measures have slowed transmission of the virus, while spawning new problems and exacerbating old ones.

One old problem is the ongoing opioid epidemic here in the US. A press release by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports the number of overdose deaths accelerated during COVID-19, likely due to the economic and mental health fallout of the pandemic. “The disruption to daily life due to the COVID-19 pandemic has hit those with substance use disorder hard,” said CDC Director Robert Redfield, M.D. “As we continue the fight to end this pandemic, it’s important to not lose sight of different groups being affected in other ways. We need to take care of people suffering from unintended consequences.”

Synthetic opioids (primarily illicitly manufactured fentanyl) appear to be the primary driver of the increases in overdose deaths, increasing 38.4 percent from the 12-month period leading up to June 2019 compared with the 12-month period leading up to May 2020. Overdose deaths involving cocaine also increased by 26.5 percent. Based upon earlier research, these deaths are likely linked to co-use or contamination of cocaine with illicitly manufactured fentanyl or heroin.

The CDC recommends that essential services for people most at risk of overdose remain open and that preventive and response services expand. More specifically, the CDC recommends:

- Expand distribution and use of naloxone and overdose prevention education.

- Expand awareness about and access to and availability of treatment for substance use disorders.

- Intervene early with individuals at highest risk for overdose.

- Improve detection of overdose outbreaks to facilitate more effective response.

Collaborative care teams in both outpatient and inpatient settings will undoubtedly play a role in a renewed focus on the addiction crisis in the US. However, there is an emerging concern among healthcare ranks that requires attention too. The problem is the unseen moral injury among healthcare workers.

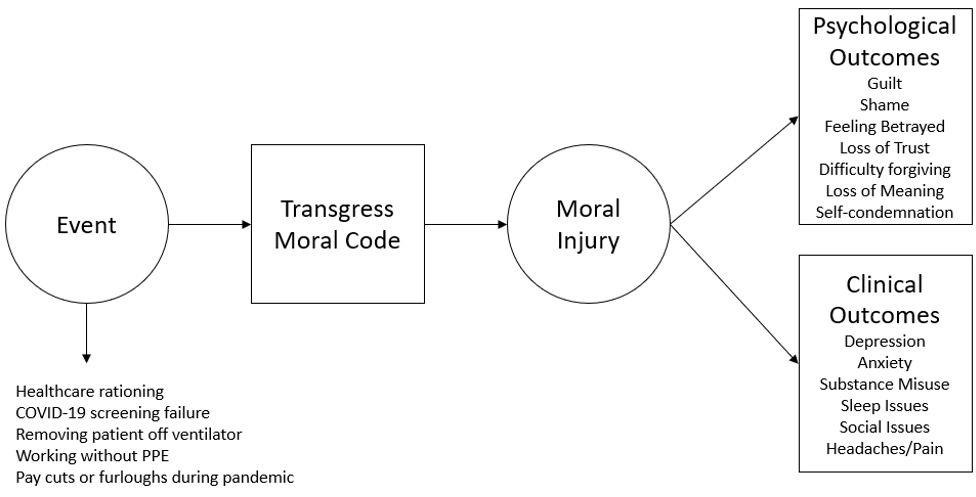

Moral injury is a normal human response to an abnormal traumatic event. See Figure 1 below. It refers to the injury to an individual’s moral conscience resulting from an act of perceived moral transgression.1 The individual experiences profound emotional guilt and shame, and in some cases also a sense of betrayal, anger, and intense moral disorientation.2

Although primarily studied in military populations, there is wider attention being given to the moral injuries of healthcare workers amidst the pandemic.3,4 Examples of potentially morally injurious events include taking a patient off a ventilator to make it available for other patients, failing to properly screen a patient, resulting in other vulnerable patients’ exposure to COVID-19, and bearing witness to the rationing of healthcare resources that may have helped save lives.

Moral injury occurs when healthcare workers avoid or suppress painful moral-sourced emotions and thoughts, resulting in greater suffering that negatively impacts the person’s ability to care for patients and work with colleagues. There is some evidence that moral injury predicts later development of PTSD.5 Overall, we know little about moral injury in healthcare.

There are calls from opinion leaders and researchers for more investigation into moral injury, a critical requirement for developing tailored evidence-based prevention, assessment, and treatment methods. Some solutions may include expanding access to mental health services for healthcare workers or requiring team decision-making when rationing life-saving treatment resources. Healthcare workers are a precious resource in our society, as evidenced by the pandemic, and deserve the right support at the right time to do their job. We cannot assume the current pandemic will end without ramifications.

References

- Barnes, H. A., Hurley, R. A., & Taber, K. H. (2019). Moral injury and PTSD: often co-occurring yet mechanistically different. The Journal of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences, 31(2), A4-103.

- Litz, B. T., Stein, N., Delaney, E., Lebowitz, L., Nash, W. P., Silva, C., & Maguen, S. (2009). Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: A preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clinical psychology review, 29(8), 695-706.

- Dean, W., Jacobs, B., & Manfredi, R. A. (2020). Moral injury: the invisible epidemic in COVID health care workers. Annals of Emergency Medicine.

- Borges, L. M., Barnes, S. M., Farnsworth, J. K., Bahraini, N. H., & Brenner, L. A. (2020). A commentary on moral injury among health care providers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy.

- Borges, L. M., Barnes, S. M., Farnsworth, J. K., Bahraini, N. H., & Brenner, L. A. (2020). A commentary on moral injury among health care providers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. https://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/2020-39196-001.html

Leave a Reply